Propoganda posters - What are they good for?

Any historian will tell you that tanks, missiles, guns, and bullets only take an army so far.

When it comes to war, military heads and national leaders need other, more sophisticated weapons in order to make sure the people handling the artillery are doing so with a sense of willingness, purposefulness, and national pride.

Propaganda is one of the most effective tools when it comes to manufacturing broad consent.

In the 20th Century, with the development of mass-marketing and mass-distributing technologies, nations across the world found incredibly effective ways of using propaganda. What better way to do that, than with propaganda posters.

In this article, we’re going to take a look at how five of the most dominant countries of the 20th Century used propaganda posters to create social consensus, especially during wartime.

Propaganda posters the United Kingdom

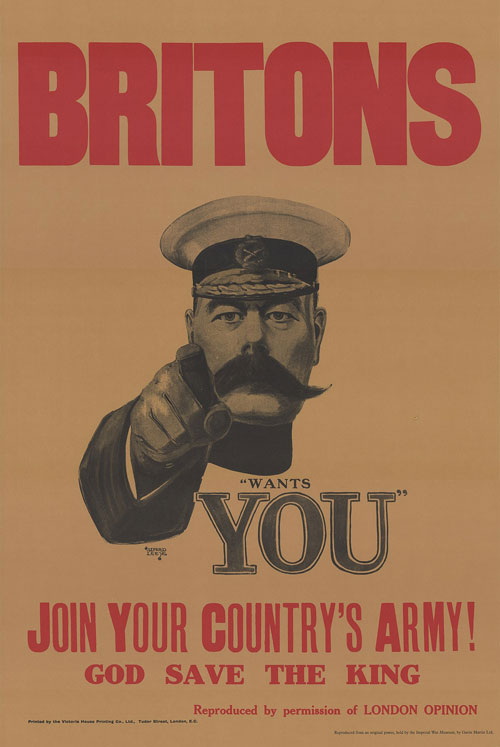

Britons Wants You - Alfred Leete (1914)

Officially called ‘Lord Kitchener Wants You’, this poster was created by Alfred Leete in 1914, as a recruitment poster at the start of the First World War.

Kitchener, The British Secretary of State for War, points directly to the viewer, in a way that feels very personal.

The image was incredibly iconic, very effective (it may have driven as many as 1 million people into the Army, along with other propaganda posters), and has been imitated repeatedly by other nations.

Britons Wants You – Alfred Leete

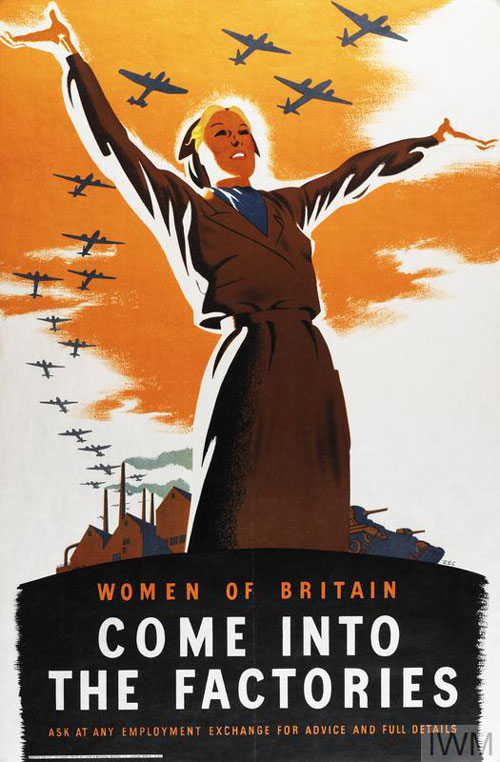

Work in Britain (Women of Britain) – Philip Zec

Work in Britain (Women of Britain) - Philip Zec (1941)

With war affecting every part of life in Britain in 1941, this poster was aimed at getting women into the workplace, in order to keep the economy moving at a time when many men were off fighting.

The image reflects a similar Soviet propaganda style, with the woman presented as monolithic and exultant. And, as with Soviet propaganda, this poster was incredibly effective.

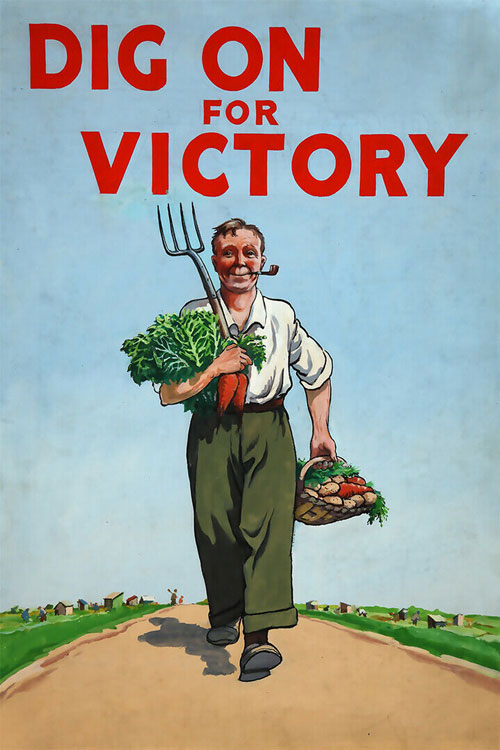

Dig for Victory - Peter Fraser (1941)

The ‘Dig For Victory’ campaign encouraged men and women across the country to grow their own food, as strict rationing was having an effect on the food supply.

In a very powerful way, the poster taps into the idea that every citizen in a nation could ‘play their part’ or ‘do their bit’ for the war effort.

Dig for Victory – Peter Fraser

Propaganda posters of the USA

Uncle Sam Wants You – J. M. Flagg

Uncle Sam Wants You - J. M. Flagg (1917)

Taking inspiration from Britain’s ‘Lord Kitcher Wants You’ poster, the American war effort moved to gain a similar emotional response with their ‘Uncle Sam Wants You’ poster.

The poster is perhaps better and more memorable than the British one because Uncle Sam is considered a personification of the entire country, while Lord Kitchener was merely a politician.

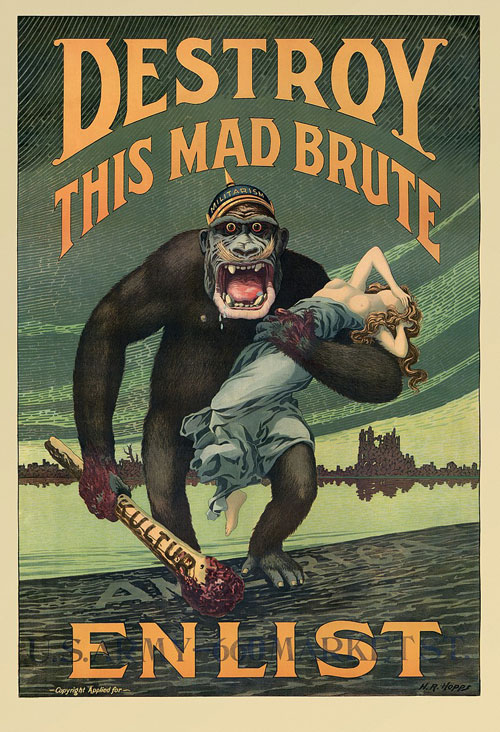

Destroy This Mad Brute - Harry R. Hopps (1917)

The US entered the First World War late into the game. And, as such, they had to sell their involvement in the war to the sceptical general public.

Images like Destroy This Mad Brute played into one thing: fear. The fear that a crazed, weapon-wielding, animalistic German would invade American soil and steal its women. It may have been base, but it was certainly effective.

The takeaway? Dehumanising your enemy is sadly an important part of war propaganda.

Destroy This Mad Brute – Harry R. Hopps

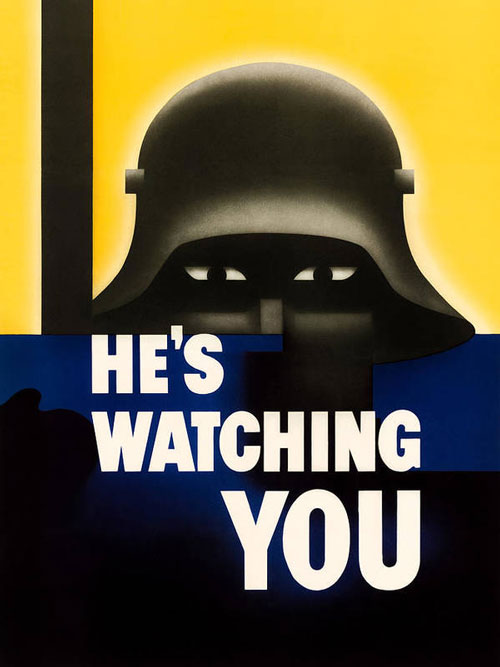

He’s Watching You – Glenn Ernest Grohe

He's Watching You - Glenn Ernest Grohe (1942)

Three years into WWII, the Nazi helmet had already become something of a synecdoche (a part that represents the whole) to depict the US’ wartime enemy, which is why this propaganda poster is so effective.

It was aimed as a precaution against the influence of Nazi spies, but also served to further engender fear about the Nazis themselves. And, if it reminds you of Darth Vader’s helmet, then hey presto, you now have a sense of how well this propaganda worked.

French propaganda posters

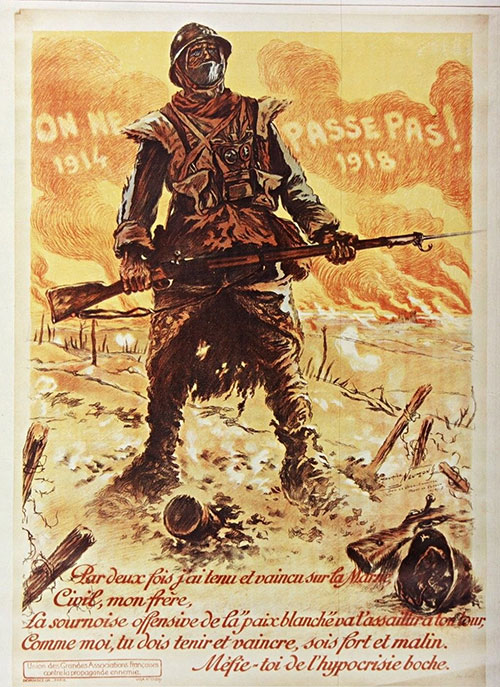

“They Shall Not Pass” - Maurice Neumont (1918)

A slogan that became famous in France in 1916, it resulted in the 1918 poster, On ne passe pas!, by artist Maurice Neumont.

In a war where deep trenches were dug and extensive battle lines were drawn, soldiers who maintained their lines and stopped others from ‘passing’ were considered the ideal, the heroes – which might explain this poster’s effectiveness.

The phrasing went on to be used by Spanish Civil War fighters (“No pasaran!”), as well as countless other armies.

“They Shall Not Pass” – Maurice Neumont

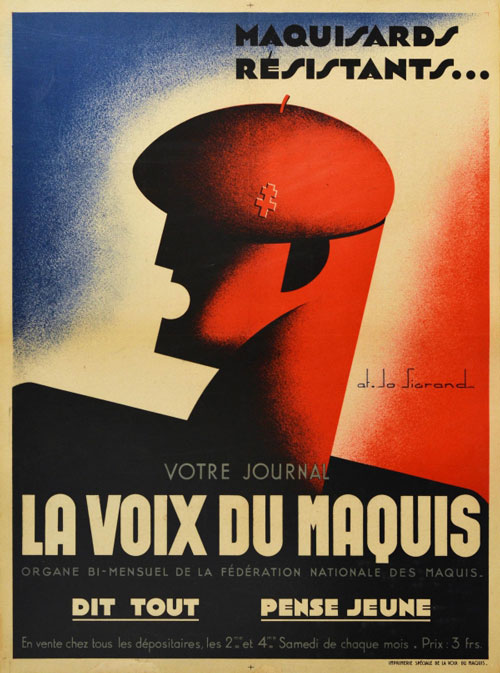

The Voice of Maquis – Jo Sigrand

The Voice of Maquis - Jo Sigrand (1940s)

The Maquis French Resistance fighters were a group of partisan fighters who resisted the Nazis in WWII.

In this propaganda poster, the French soldier is depicted in an Art-Deco style. The geometrics are interesting here. Look at the hardened jawline. Look at the straight nose. Look at the mouth open as if in protest. This is an idealised, stylised, fighter – one that other Frenchmen might aspire to be like.

To be Silent Is To Serve - Georges Lang (1940)

It’s important to remember that new information technologies were part of the weaponry of WWII. Unlike the wars preceding this, a spy or infiltrator could gain easy access to a telephone, where they could relay the secrets of an opposing army in real-time. Therefore, one of the key messages early on in the war was the need for silence and secret-keeping.

This poster is fairly self-explanatory in that regard. But in terms of messaging, you might note how it stresses the idea that everyone in France can ‘do their part’ in the war; note how simply being silent is depicted as ‘service’.

To be Silent Is To Serve – Georges Lang

Germany's Nazi propaganda

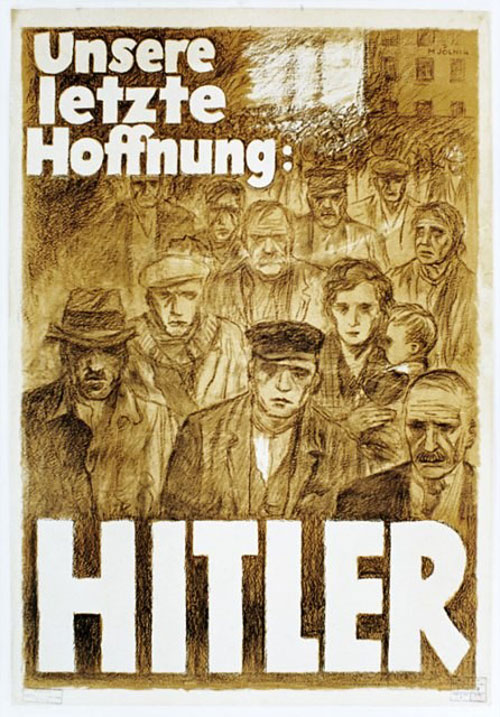

Our Last Hope – Hitler – Mjölnir [Hans Schweitzer]

Our Last Hope - Hitler - Mjölnir [Hans Schweitzer] (1932)

Most dictators and authoritarians will plot their path to power by suggesting that the ‘end times’ are right around the corner. In the 1932 German elections, the Nazis did just that.

With ghostly depictions of hungry citizens (this was three years into The Great Depression, don’t forget), this poster carried the message that this would be the last opportunity Germans would get to save themselves. As propaganda goes, it doesn’t get much more compelling than this.

The People's Car - KDF (1938)

As the early 20th Century wore on, automobiles were becoming more and more common in regular households.

Taking note of this, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler saw a way to wed this trend with the idea of national identity. The ‘Volkswagen’ (People’s car) was meant to be for everyone in Nazi society. Its imagery reflects everyday working Germans in their automobiles, perhaps proud of their small but important contribution to the national effort.

The People’s Car – KDF

Liberators – Harald Damsleth

Liberators - Harald Damsleth (1944)

If American propaganda posters tried to dehumanise their German enemy, the Nazis did the same – only sometimes it was a bit weirder.

This poster was designed by Harald Damsleth and was meant to depict a monstrous personification of America, with all its worst qualities – the KKK, slavery, lynching, and capitalistic excess – all brought together. It calls on the viewer to really look at it, which might be what makes it function so well.

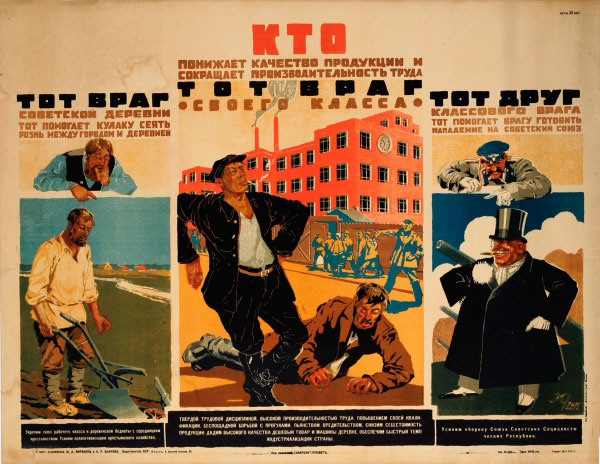

Russia/Soviet Union's propoganda machine

Build Tanks - El Lissitzky (1941)

Soviet posters were often powerful rallying cries to the general populace, exhorting them to do their part for the communal effort.

As with other recognisable avant-garde Soviet posters, this poster’s composition is interesting; it involves workers staring purposefully into the distance, while the artillery – tanks and planes – sit at an angle moving upwards from left to right. The effect is to make this propaganda poster seem forward-thinking and it hints at innovation.

Build Tanks – El Lissitzky

The Emancipation of Russian Women – Adolf Strakhov-Braslavsky

The Emancipation of Russian Women - Adolf Strakhov-Braslavsky (1926)

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, it became necessary for propagandists to continually highlight the changes they were bringing into Russian society.

Strakhov-Braslavsky’s ‘Emanicaption’ poster – his most famous – helped stress the role of women in Soviet society. Look at the purpose on the woman’s face here. Look at the fully operating factory behind her. Look at what she’s carrying – either a piece of working equipment or maybe even a weapon.

It’s clear that women were to be fully integrated into this new, prosperous society.

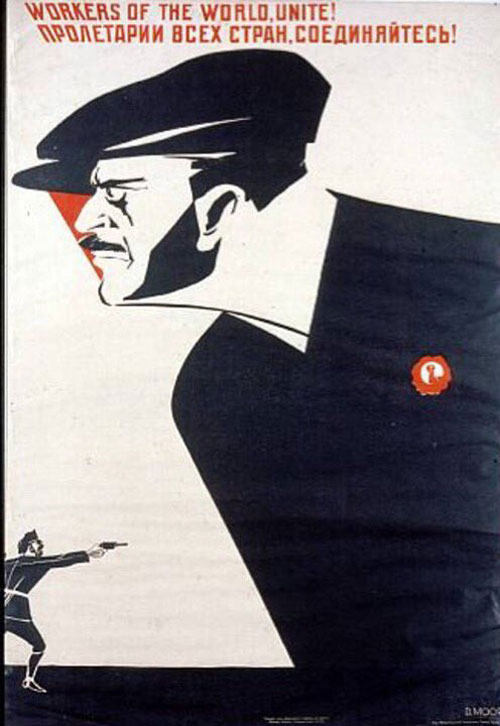

Workers of the World Unite! - Dimitry Moor (1931)

In the decades between the two World Wars, the Soviet Union used propaganda posters to help portray itself as unified, in contrast to the chaos of competing ideologies and societal breakdowns which were happening in other countries during this era.

In the ‘Workers of the World Unite!’ poster, Dimitry Moor uses Karl Marx’s famous phrase alongside an image of a sternly-depicted Soviet worker resisting the influences of everything from capitalism, to fascism, to organised religion.

Workers of the World Unite! – Dimitry Moor

Propoganda and National Identity

When you break them down, nations are just imagined communities. The idea of a single ‘national identity’ isn’t an organic one, but one that is socially constructed. Propaganda posters had an important role to play in that construction.

And how effective is it? You only need to look at the evidence from the 20th Century to see how powerful propaganda was. It encouraged people to embrace a sense of national belonging, it caused them to hate or mistrust people from other countries, and it led to many millions marching off to their deaths in service of someone else’s purpose.