Soviet Avant-Garde

The years following the First World War saw major changes in all of the most powerful countries of the world, with empires collapsing, ideologies competing, and new cultural movements vying for their place.

But nowhere changed as rapidly and comprehensively as Russia/the Soviet Union. In the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet Union underwent a cultural shift that redefined the meaning of the word ‘radical’.

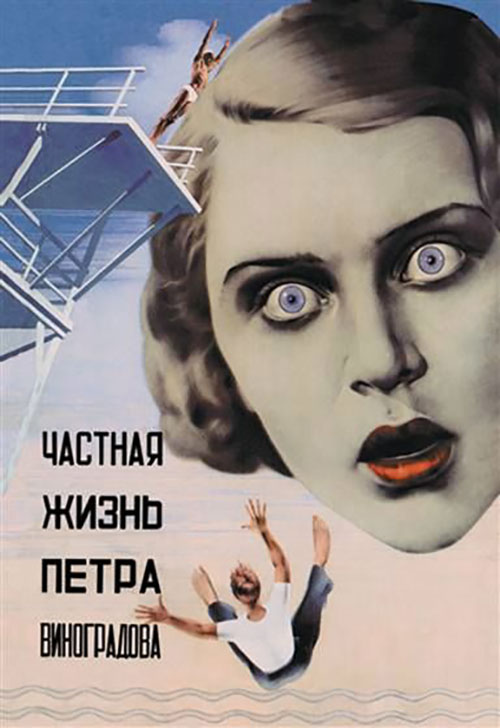

This was most apparent in its new ideas in art – and, in particular, with Soviet Avant-Garde movies and their posters. These posters, which were ostensibly promotional tools for films, took on lives of their own, showcasing the strange new places where Soviet artists had found themselves working in.

Many of the posters below are considered definitive works of Soviet art, and most of them have had a longer legacy than the movies they were designed to promote.

Let’s take a look at 11 posters that helped mark this radical art movement.

The Man with a Movie Camera - Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg, 1929

The Man with the Movie Camera, directed by Dziga Vertov, is a quintessential filmmaker’s film, noted for the fact that it was one of the first films to employ new techniques such as slow and fast motion, split screen, and montage.

The film’s accompanying poster, which was designed by Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg (you’ll be reading their names a lot in this article), gives a taste of how ambitious Soviet Avant-Garde artists were.

Look at the disassembled body parts pressed flat onto the poster like a collage. Look at the dizzying high-rise architecture. Look at how the typography spirals rather than moving from left to right. This is as far from a ‘standard’ Western film poster as you can get.

One of the most revered and important Soviet graphic designers, Anatoly Belsky became a leading film poster designers in the 1920s.

Belsky came to the fore at the same time as Soviet filmmakers began to really utilise the possibilities of montage (like Vertov, mentioned above). Montage also had a massive influence on poster designs, as it offered new opportunities in terms of perspective, proportions, and how much you could get away with presenting to the viewer on the poster (many artists and filmmakers alike had previously conservative with their poster designs, but montage – to put it bluntly – encouraged them to weird).

Belsky’s poster for The Communard’s Pipe is inventive enough as it is, with human bodies coming through the tendril of smoke emerging from the pipe – but everything from the proportions of the people depicted here, to the almost blanched colouring of the young boy Jules who is smoking the pipe, begs your eyes to studying it in-depth.